Some of my friends still have inside jokes about this particular genre. Gone are the days where the archaic art teacher would bring in raw fish and plonk them on everyone’s desks for an art test, or rearrange a basket of fruits almost to clinical perfection for a very serious evaluation of a child’s artistic prowess.

The underdog within the hierarchy of Art, ‘nature morte‘ or dead nature is a genre that is anything but dead to me. Let’s be real. In every rom-com, everyone would like to see the underdogs win. Still-life pictures are the very antihero of artistic society . Unassuming and seemingly unappreciated, everyone secretly wants to cheer it on. For as we know, every artist who has had to make his or her mark has to attempt on some highly imposing composition involving ridiculously complicated human figures.

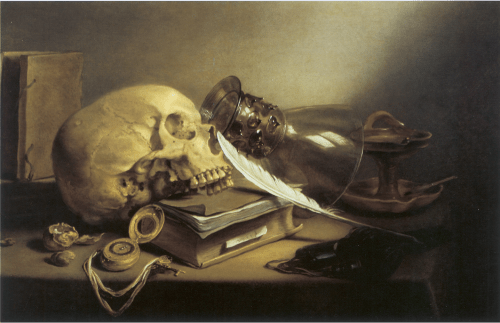

Yet there is a quiet dignity in still-life, and each image can completely be symbolic or representative of it’s age. Think of the moral story behind every Flemish vanitas or the austere darkness of Spanish bodegones. Who needs an audio guide in the museum for a complete recount of what they encapsulate?

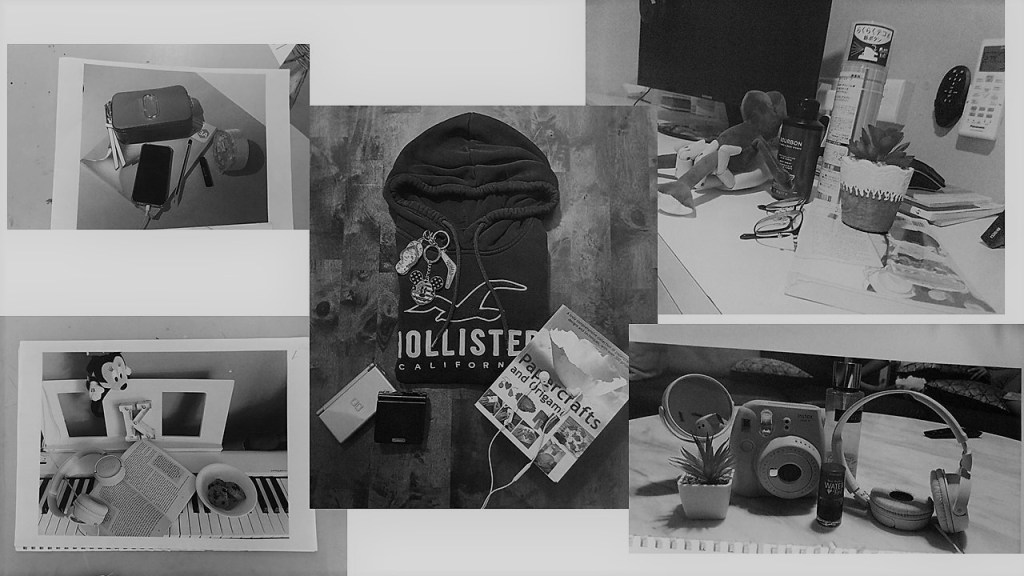

In our age, the repertoire of still-life far extends only paintings. A photographer takes a snapshot of an office desk to include in a brochure. An influencer’s casual snapshot of items put together for a ‘what’s in my bag’ post. A makeup artist revealing all the products she used on the latest Hollywood starlet. They are all vignettes of today’s life, documenting contemporary life as much as a prized monument in the piazza of an Italian city.

Fans of Spiderman know that ‘with great power comes with great responsibility.’ In this case, do I dare say that with great affluence comes great complacency? With the rise of thriving prosperity in the Low Countries, it was imperative that one must never forget one’s mortality, and to continue to live life full of integrity. It is no wonder that one would repeatedly find the human skull starring in most vanitas pieces. Sometimes one would find a less obvious symbol, such as an insect or a dying leaf on a beautiful bouquet in full bloom hinting at decay or decomposition. One can safely say that the fear of any wealthy seventeenth century Flemish is pretty much encapsulated in the genre.

The Spanish, at the beginning of the century, took an entirely different approach to things. Juan Sánchez Cotán was the trailblazer for bodegones, synonymous with ‘tavern’ and subsequently used to refer to still-life paintings in the country. Still Life with Game Fowl features a composition that almost resembles an altar of pantry items. These items set deliberately apart from each other, divided and isolated in an almost reverent manner. The luxurious materiality of vanitas is not found in bodegones. Present is the strange juxtaposition of an aura of severity that is mysteriously expressive.

As is the case with vanitas, these bodegones offered a lens into Spanish preoccupations at that time, not excluding Baroque sensibilities and Catholic Mysticism that was so important in society. The iconic simplicity and emotive quality of such worlds can be seen most succinctly in Francisco Zurbaran’s ‘Agnus Dei‘. Here, we can actually barely call it a composition with just a single lamb at the centre of the layout. However, if a picture could tell a thousand words, this painting would be perfect in summing that up. The meanings that this painting exudes is a millionfold and speaks to me much more than any impressive masterpiece can. I guess Zurbarán truly lived closely by the Baroque manifesto of creating art that touches the heart directly.

Francisco de Zurbarán , ‘Agnus Dei’, 1640

So how would this genre be presented as a sign of our times? The question to ask ourselves is what are we concerned about as a society today? What is the skull that represents mortality if we were to do a contemporary version of a vanitas? How would we arrange our items to resemble an altar of our faith as Señor Sánchez Cotán did? As Aristotle once said ever so rightly, ‘the aim of art is to represent not the outward appearance of things, but their inward significance.’ Here are a couple of still-life images my fifteen year old students attempted. They are still feeling away in the dark trying to understand the complex world of Art, but one thing for sure is that every decision they do make reflects their self-identity and how they relate to this present world. I will let you decide on the inward significance of their own version of the genre. What can you read about the world of today from their humble still-life images? Let’s do a little role reversal , and let my students be the teachers today.

Leave a comment