Doors fascinate me to no end. Their meaning is many fold. Secrets, possibilities, surprises, transitions among many others. Their function is multiple. To draw in, to keep out and to lead somewhere. It is no wonder then that they are one of the firm favourites of Surrealists when picking out a subject matter, using them as a portal to the subconscious.

Indeed as Daniel Kershaw, museum design manager at the Metropolitan Museum of Art a.k.a door aficionado once so rightly said, ‘great art themselves act as doorways to something else’. One can then also say that Surrealism itself is a door to many possibilities. It is hence an interdependent relationship that is forged right here between art and muse, represented by Surrealism and doors. Since the art movement itself seeks to reconcile real life with the alternative world that lies in dreams and the unconscious, doors acts as a medium to unite both worlds.

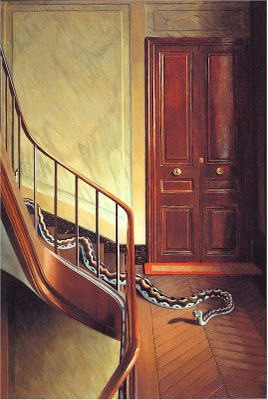

In their efforts to wrench things out of their original context (so that the subject matter is not inhibited by their cultural constraints in their original setting), displacement is a tool that surrealists employ repeatedly. Pierre Roy’s Danger on the Stairs features a door in a seemingly normal backdrop until one spots writhing anaconda on the steps. The door is fixed firmly behind the massive serpent and there is no escape. The sense of being trapped is further amplified by the fact that viewer only has two ways to escape, namely the mundane stairwell as well as the unassuming door These two possibilities are however, convenient blocked by the strategic placement of the creature, elevating the sense of fear and danger.

By displacing the anaconda from its usual setting and placing it against the stairway, one’s worst nightmare comes true. It’s been said that Roy himself had ophidiophobia, and his choice in placing a snake in this picture was not random. This ordeal comes alive especially for the artist as the stairway echoes the type of quintessential French apartment that the artist himself spent his own childhood in. This category of horror usually falls under the irrational and lurks in the depths of the mind (most people would have the good fortune to not chance upon an anaconda in such circumstances) is now being featured in the bright light of the day, not even bothering to hide in plain sight.

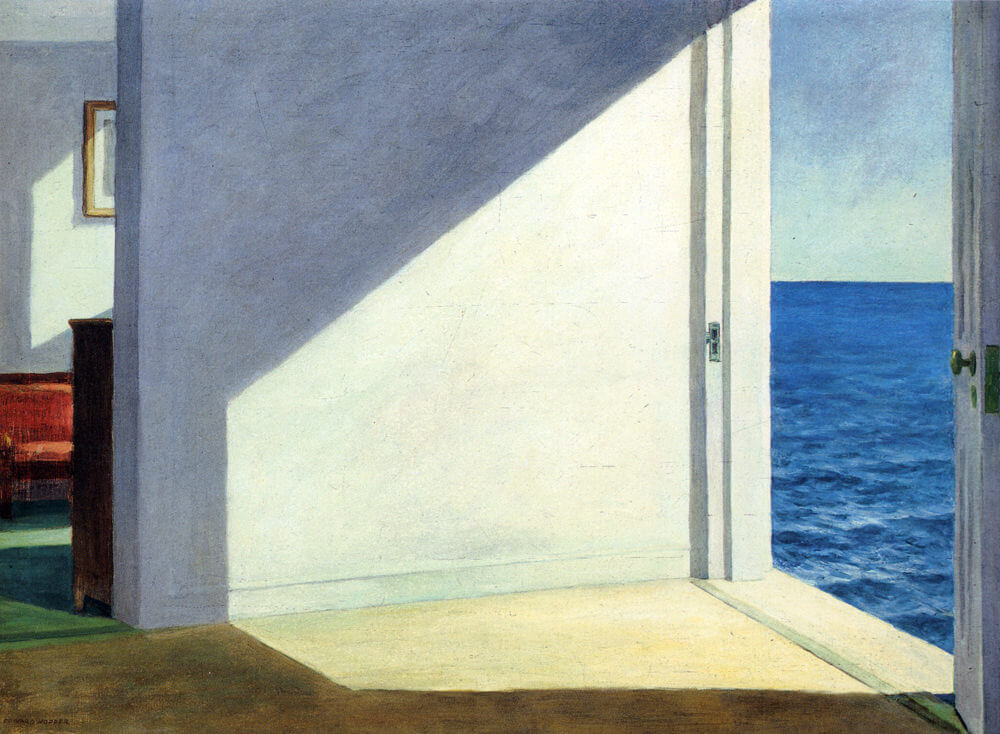

Other than playing a part as a lackadaisical backdrop against which fantastic objects contrast against, doors are also used to symbolise secret places inside the subconscious. By leaving an opening to invite the viewer to enter, the psyche of the artist is revealed to a privileged few who have the courage accept this invitation.In Edward Hopper’s Rooms by the Sea, an open door that is featured revealing his studio overlooking the water at Cod Cape Massachusetts. The sunlight pours into the room, while the outside reveals a gorgeous seascape. It seems that Hopper is painting his view of the back door of his studio but this picture is really a visual metaphor of his solitude and introspection. Similarly, in Kay Sage’s My Room has Two Doors, she uses the same device to depict a similar sense of introspection and loneliness. Here , her painting has two doors, giving one hope that escape is possible should one choose to do so. However, as Danger on the Stairs, there is really no way out. In this metaphysical space, the red door featured here symbolises the hope of a new life, yet this door cannot be opened. A similar sense feeling of loneliness and isolation is felt here as in Hopper’s work, amplified by Sage’s accompanying poem.

My room has two doors

And one window.

One door is red and the other is gray.

I cannot open the red door;

The gray door does not interest me.

Having no choice,

I shall lock them both

And look out of the window.

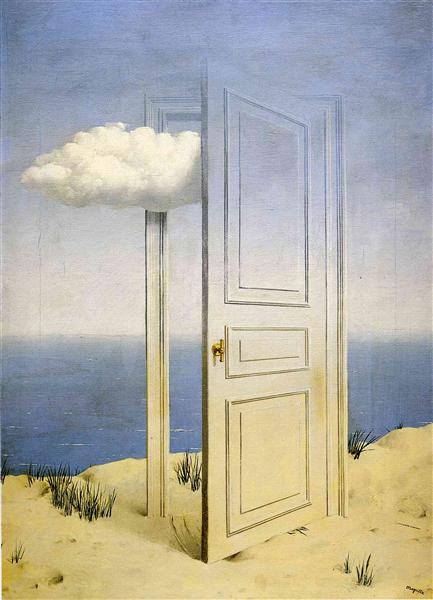

What if there is no escape not because one is locked in, but rather, the other world that awaits on the other side of the door is entirely the same as the one you just stepped out of? Would one find some sort of reprieve in that? Or is one is still trapped in another image that has its own cruel way of locking somebody in? In Rene Magritte’s The Victory, he places his door against the backdrop of a seascape. The door is ajar and leads out to…the same seascape. Wait a minute. Don’t open doors lead to new possibilities? Would you venture out to the infinite space that looks just like the one on the other side of the door? Would one bother? In The Victory , there is no physical constraint or barrier as in Danger on the Stairs, but the one finds a door and yet doesn’t find the way out. Such is the danger of the subconscious and dreams. Exiting on your own terms is never an option.

The merging of internal and external space was also used by Magritte’s predecessor Giorgio De Chirico in ‘Conversation Among the Ruins’ , where a man and a woman who are seen in dialogue. The seemingly anachronistic pair is oddly exist in in the same abstract space, untouched by time although the man is in a rugged contemporary suit while the woman is gracefully garbed in a classical Grecian robe. Here, a doorframe hovers, but it doesn’t rest on a wall. The conversation looks uncomfortable and should be taking place behind four walls that don’t exist here. The pair doesn’t seem to have healthy physical boundaries between them as the male intimidates the lady with his body language. This is echoed in the landscape as one looks beyond the door and the same interior space encroaches into the exterior. Or is it the exterior that creeps into the interior? The lady is obviously uneasy while she is longingly looking up at the Greek hero whose angle interestingly mirrors her intimidator. The only way she can excuse herself from this uncomfortable dialogue is to wake up from this strange, strange dream for the doorframe does not offer one the option of going to a different place.

Dorothea Tanning, the wife of Max Ernst , and established Surrealist in her own right, also once vividly described a dream that she herself would have liked to flee from. ‘I do recall I had a dream about doors a long time ago, and those doors appeared in many canvases afterward. It was a horrible dream. I opened it and it was another door right behind it.’ Since that significant episode, works in Tanning’s oeuvre subsequently featured the subject matter repeatedly. Doors were repeatedly depicted used in her art. In Eine Kleine Nachtmusik, an unsettling atmosphere found in a hotel corridor is filled with a gigantic sunflower as two creepy girls seemingly in a trance roam about almost as if they were sleepwalking. One of the girls lean against a close door while a faraway portal is ajar, almost beckoning one to discover what lies behind. However, one would wonder if awaits on the other side would offer some solace from this strange place, or has even worst horrors awaiting? One only has to take a gamble and decide.

In Maternity, a woman in a torn nightgown holds a baby against a backdrop of an arid landscape with a doorframe in the centre. A puppy with a face of a cherub lifts the atmosphere with its smile and enthusiasm. The door is open, and the woman is faced with some serious decision-making represented by the open doorframe. However, the lady does not seem too pleased with what is presented in front of her. Does she have to choose the lesser of two evils that we can’t see? The door is obviously open, but that option does not seem too palatable. The iconic ‘Birthday’ sees Tanning portraying herself (at the age of thirty two years old) with her hand on the doorknob, although it is unclear if she is opening or closing the door. In her own words, she says, ‘everything is in motion. Also, behind the invisible door (doors), another door … There is no showing who one really is.’ Perhaps even Tanning doesn’t know if she wants to keep the door open to the endless possibilities, varied versions of her self identity. Which door out of the many in the passageway would offer her some clarity? Should she close the door or leave it open?

Of course, for the painter, some doors should be left firmly shut. In Door 84, she features a door set ablaze with hurried exuberant brush strokes mirrored by the dynamic posture of the two figures. Both women are divided between a literal door. Both women are pushing at that door in opposite directions, making the event a rather fruitless one. Energy pulsates through this electrifying piece not least because one feels both women giving their all in breaking the door open. I can almost imagine a ‘high voltage’ warning that might come with this work. What should further be indicated on this hypothetical warning would be ‘do not open door’, a warning that Tanning herself has uttered while addressing this Door 84. One can only speculate what that door means for Dorothea. Indeed, doors, whether they are opened or closed, do not necessarily offer one the chance to go to where the grass is greener. The presence of doors themselves are just an illusion, as much an illusion as is the painted door itself. But fret not, for the saying goes, when God closes a door, he always opens a window. One only has to keep feeling around in the dark, barren land to get to a better place where flowers bloom and souls can thrive.

Leave a comment