Art enables us to find ourselves and lose ourselves at the same time. It teaches us to seek what we need, and sometimes be willing to completely lose ourselves on this journey. Being my constant companion on this journey of life, art has always been indispensable in my road to self-discovery. In particular, an art movement that I have always been partial to has taught me more than a thing or two about life. From the Portuguese word ‘barocco’, meaning ‘irregular pearl or stone’, my favorite art movement was one created from early seventeenth to mid-eighteenth century, and was a consequence of a cultural and religious shift that sought pressing new ways to reinvent art. Moving away from the fruitless search for ideal beauty, proponents of Baroque art instead searched for what I perceive to be authentic beauty. This type of beauty to me, is one that is inclusive, relatable and is ultimately realistic in terms of standards. On the way to forge this impressive new standard of aesthetics, many values were cultivated and propagated that ultimately inspired a new way of creating, seeing and living.

Going back to basics.

With the Catholic Church facing unprecedented challenges with the rise of the Reformation, many artistic problems that arose during the Renaissance were multiplied. This included the perennial problem of figurative subject matters in sacred imagery. While the Renaissance brought about the invention of artistic techniques that created incredible illusion in painting and sculpture, it was a double-edged sword as they made it difficult for one to differentiate between truth and reality. Protestants charged the Catholics for using images improperly as a results as the latter sometimes had the tendency to sometimes worship images of Christ, Mary, or the saints as if they were present in the images themselves. They also found Catholic practices such as touching, kissing, and talking to images idolatrous. As such, art was clearly part of the problem, but subsequently became a integral part of the solution. It was in this moment that the humble genre of still-life saw a comeback during the 17th century. Previously regarded as a lowly genre, various renditions of still-life made a comeback in this period throughout Europe. Some examples included Spanish Bodegones, Dutch Vanitas and endless variations of the category. Bodegones even rose to the heights of other genres regarded as worthier. In Italy, Caravaggio famously said that it took as much skill “to do a good picture of flowers as of figures.” The genre was so popular that still-life subject matters were even combined with figures in a simple composition and they co-starred together to form arresting images that captivated the viewer in an inventive way. As we can see, sometimes it’s essential to go back to basics when reinventing oneself.

Simplicity is key.

During the Renaissance, the search for perfect beauty, balance, symmetry and grace was rampant. Simplicity however, was not a preoccupation for the proponents of the movement. Compositions were becoming incredibly complicated as artists sought to prove their intelligence due to their newly minted elevated status. This was highly ironic as art’s fundamental function was to teach the bible to the illiterate masses and simplicity was a key component in the comprehension of images. The great Baroque artist, Caravaggio made several artistic innovations, but one notable one was in simplifying his figures to a half length, allowing the viewer a close-up of what is happening, granted them access to being part of the scene. One can see the Spanish artist Francisco Zurbaran’s depiction of the Death of St Serapion, and the starkly caravagg-esque treatment displayed here. Such close-up figures transported the viewer into the scene of the action happening , and provided clarity in the message sent. Gone was all the ostentatious and riddle filled compositions of the Renaissance that defeated the original purpose of art- to teach the bible to people who could not read. Sometimes life is simple, but we insist on making it complicated.

We all need to be dramatic sometimes.

Baroque art aimed not to persuade through reasoning or appealing to the intellect, but going straight for the heart. The power of the theatre had always had it hold in her sister arts from the beginning of Greek antiquity onwards. The seventeenth century saw an even more intense impact of the theater in the creative exchange among the various form of arts. In addition, the Council of Trent (established by the Catholic Church as part of their Counter Reformation efforts) decided that art should encourage emotional reactions to aid Christian devotees in their atonement for their role in Christ’s sacrifice and primarily move their viewers. One of the key ways they called on the power of the theatre in works of art was through dramatic lighting seen in Tenebrism. This lighting device is really a more dramatic form of chiaroscuro, and resembles a spotlight effect mirroring the ones used on stage that was created in painting through bold illumination set against plunging darkness. Usage of exaggerated dramatic poses or compositions were also often employed in Baroque paintings. On canvas that mimics a theatrical stage, emotions, tension and drama are amplified on a well-scripted image. This dynamic duo of tenebrism and dramatic gestures can be found in Caravaggio’s Calling of St Matthew, where one is greatly moved emotionally by the dramatic lighting and incredible moment where St Matthew is called by Christ.

Architecture was also not spared from the obsession on the theatre. Complicated plans, focusing on vivacious oppositions and interpenetration of spaces were used to amplify the feeling of movement and drama. Other characteristic qualities include grandeur and contrast (especially in lighting), and an overwhelming lineup of gilded statuary, rich surface treatments and a myriad of twisting elements. Architects were also brazenly applying intense colours and vividly painted ceilings. The flamboyant display of opulence, ornateness was a pointed statement of power and wealth made by the Catholic Church. We have all experienced in our lives at one point or another that sometimes when we want to be heard, being dramatic captures the attention of people and there is a higher chance we get an audience. Characteristics of the Baroque was all screaming for attention , and attention they did get.

Overstepping Boundaries.

Boundaries were beginning to be abolished in this period as can be seen in the deeper interplay between theatre and other forms of art as addressed above. Artistic media also fused with each another, what belonged to the indoor merged seamlessly with outdoor settings, and artworks featured themes of transitions. With boundaries being obsolete , new possibilities were created. One of the greatest example of multi-media art is found in Bernini’s masterpiece at St Peter’s Basilica. Integrating the lighting, the painted stucco ceiling, the architecture of the room, and the way the sculpture seems to have become a part of that interior, the apse in St. Peter’s Basilica is a fantastic example of a Baroque ingenuity. Fusing various artistic media into an unprecedented work, the grandiose effect coupled with the dynamic nature of the Chair of St. Peter, generates a moving and dramatic experience for the viewer. This solidifies the Church’s Counter-Reformation message of personal encounters with God.

Sculptures were also crossing boundaries of their usual placement in a church setting or a museum, becoming commonplace in outdoor spaces. This allowed them to be framed by the changing light conditions in the outdoors and fused with exteriors of spaces as well as other outdoor elements. One of these examples can be found in Bernini’s Triton Fountain in Piazza Barberini, as well as the current favourite tourist hotspot, the Trevi Fountain. Bernini’s other amazing work is amazing sculpture of the Greek myth of Apollo in lustful pursuit of Daphne, her beautiful lithe form in the process of turning into a tree in order to escape her fate. Here we see a transition from human to laurel tree that is seamless, organic and awe-inspiring. Bernini’s virtuoso at working the marble is indeed undeniable. As artists were given the liberty to bring their creativity and imagination to new heights, this was not possible without the bold removal of boundaries of all sorts. Sure, in life, everyone needs their own boundary, but sometimes it is necessary for one to remove barriers and step out of their comfort zone. The proof is in the pudding, and can still be seen throughout Italy and all of Europe today.

Always cater to the masses

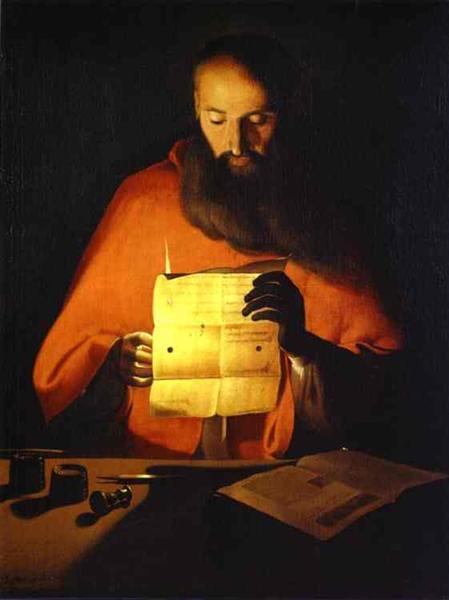

Art before the Counter Reformation was about the elite, for the elite. Characters portrayed often possessed beauty of impossible standards. In this sense, the barrier that existed from artist to audience was further lifted when more relatable models were used in the creation of sacred imagery. Instead of finding the perfect ethereal beauty of a Madonna by Raphael, we find renditions of Mother Mary who resemble everyday women in the seventeenth century. Baroque Madonnas could even pass off as someone’s mother, sister, cousin. Caravaggio even controversially went as far as using courtesans as his model for divine figures, and the supporting characters featured in his paintings were other common fold that existed in his contemporaries. His influence spread far and wide as far as France and Spain. Peasants were featured on the paintings of French artists Le Nain brothers as well as Georges de La Tour. The latter notably had the fortune of spending time in Italy between 1613 and 1616 before returning to his hometown of Lorraine. It was probably here that he acquired his taste for direct observation of lower class people and beggars. Now, we all know that the persuasive power of being able to identify with something or someone far outweighs the opposite. It also goes back to the core of Christianity seen in the following biblical text : Hebrews 4.15 For we have not a high priest who cannot have compassion on our infirmities: but one tempted in all things like as we are, without sin. Jesus was made man and can always relate to his people. He should equally be relatable to all.

It is necessary to grasp around in the dark so that one can appreciate the light.

John 1:5 The light shines in the darkness, and the darkness has not overcome it. Light and darkness coexist together. Without the darkness, one doesn’t see the light. The darker the darkness, the more fervently the light shines through. If one is being realistic, one can concur that life is a bittersweet mix of pain and joy. It is with this concept that two contrasting states of light and dark so pervasively found in Baroque art. Without the plunging darkness, one’s eye would not be able to make out the intense illumination that radiates throughout the darkness. Since darkness is something that is existential and is part of our daily life, one must learn to grapple in the dark somewhere and that light is never far. Baroque art ,in its search for unrealistic perfect beauty, embraced many aspects that were unacceptable or unspeakable. In embracing them, authentic beauty was conceived. A beauty that was tested through fire, unconsumed but refined by adversity. It was also through this new aesthetic created that the Catholic church was able to redefine their perspective. They say that art imitates life. Sometimes life also imitates art. It is essential that we take the truth and beauty in them to add a little wisdom in living this life.

Leave a comment