Hi friends! I am ashamed to say that this post is 5 months overdue. It is nearly June, which means that this post has been saved in my draft folder for more than 4 months! I have had a change of environment after staying at my last school for ten years so it took every ounce of energy in me to survive a new environment. A new workplace was not the only change in my life. Indeed, if 2023 had a theme song, it would probably be Winds of Change by the Scorpions due to the cosmic overhaul that was happening in this milestone year making it the year of many ‘firsts’. Excuses aside, I want to recount that during the last few weeks of 2023, I finally went on my virgin trip to Saigon (as one of my last on the long list of ‘firsts’ of 2023) to bid goodbye to the year that just swept through in the blink of an eye. On my third day there, I decided to check out the HCM Museum of Fine Arts. As usual, I tried to do a search on Google for information before going to the museum and could not find information as readily as I would have liked, so here I go, hoping that this post would serve anyone who requires any more info about the place.

The Compound

The ticket price is pretty standard for any entry to most places at 30,000 VND which roughly translates to $1.64 SGD or 1.10 Euros. Like many places in Vietnam, there was no air-conditioning there although I have to say that I did enjoy the balmy tropical heat throughout Ho Chi Minh with their large open spaces and fans. There was just something deeply retrospective and idyllic about such places. The HCM compound was no exception and felt especially welcoming with its central courtyard filled with several sculptures scattered around. Architecturally breathtaking, the building is a culmination of Art Nouveau and Eastern elements making a unique blend of gorgeous details that stands still in time with the ability to bring one back to a past era. The facade was tinted in a hue of soothing pastel yellow which further added to its vintage appeal and charm. Upon entrance, near the stairwell, a vintage elevator stands elegantly. This elevator, not unlike a Chinese palanquin, was no less than the first of its kind in Saigon making it deeply significant historically and culturally on top of its imposing visual impact.

The collection prides itself in housing, preserving displaying typical Vietnamese collections of art. I honestly do not recall if audioguides were offered, but I did not recall such a booth, which made the navigation experience a little left to be desired. In addition, it was pretty difficult to have a genuine artistic experience as there as there were many visitors who were more concerned at taking selfies or taking pictures of themselves looking at artworks which effectively blocked my route in the museum. Unfortunately, this was a ubiquitous problem that I found during most of my museum visits in HCM. As what I deem to be an official nod to the existence of this issue was the fact that there is a surcharge of 300,000VND to snap pictures with a professional camera within the compound. I did feel mildly irritated that museums seem to exist for people to have their Instagram moment rather than for people to enjoy the arts. However, I do acknowledge that it might also be a good way to draw people to the location and maybe ignite some interest in the display items while they are taking their Instagram photo of the day? I would really love it if they imposed this surcharge on people having photoshoots with their mobile phones, but I guess 300,000 isn’t going to be a big deterrent for museum visitors anyway.

The Collection

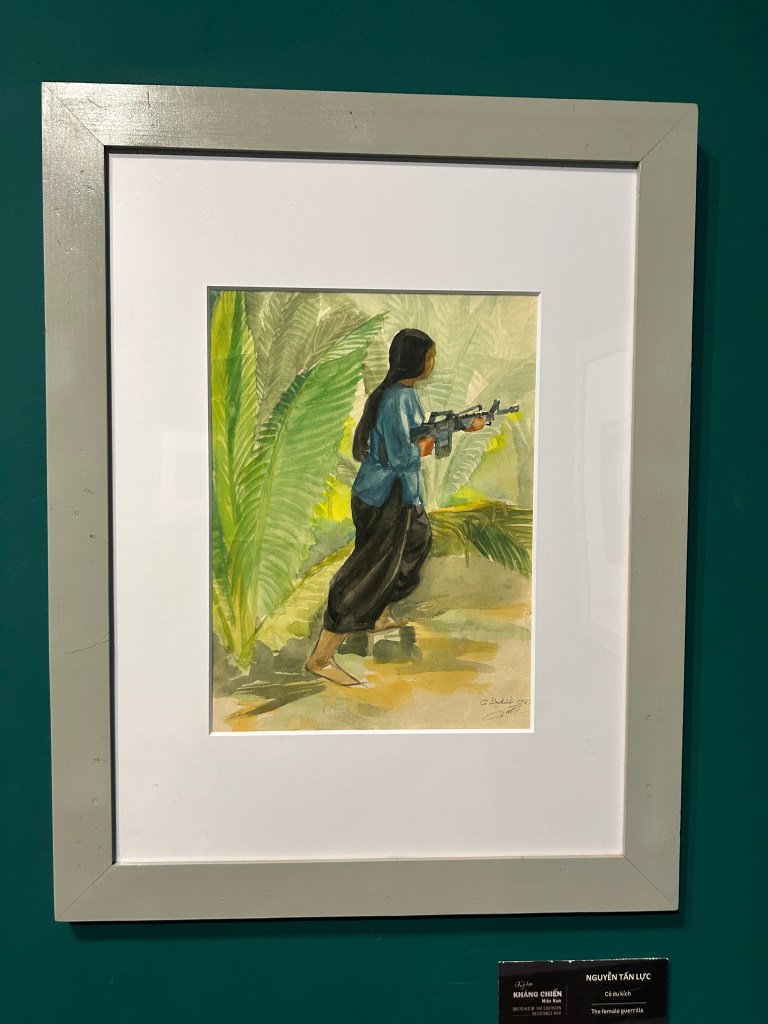

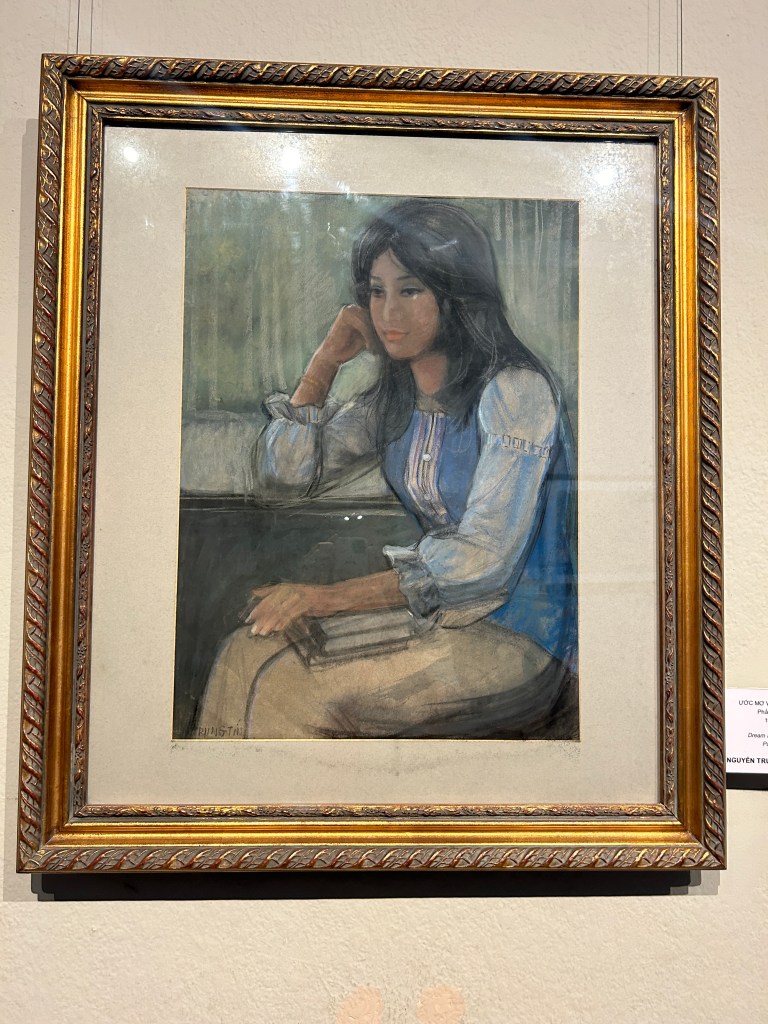

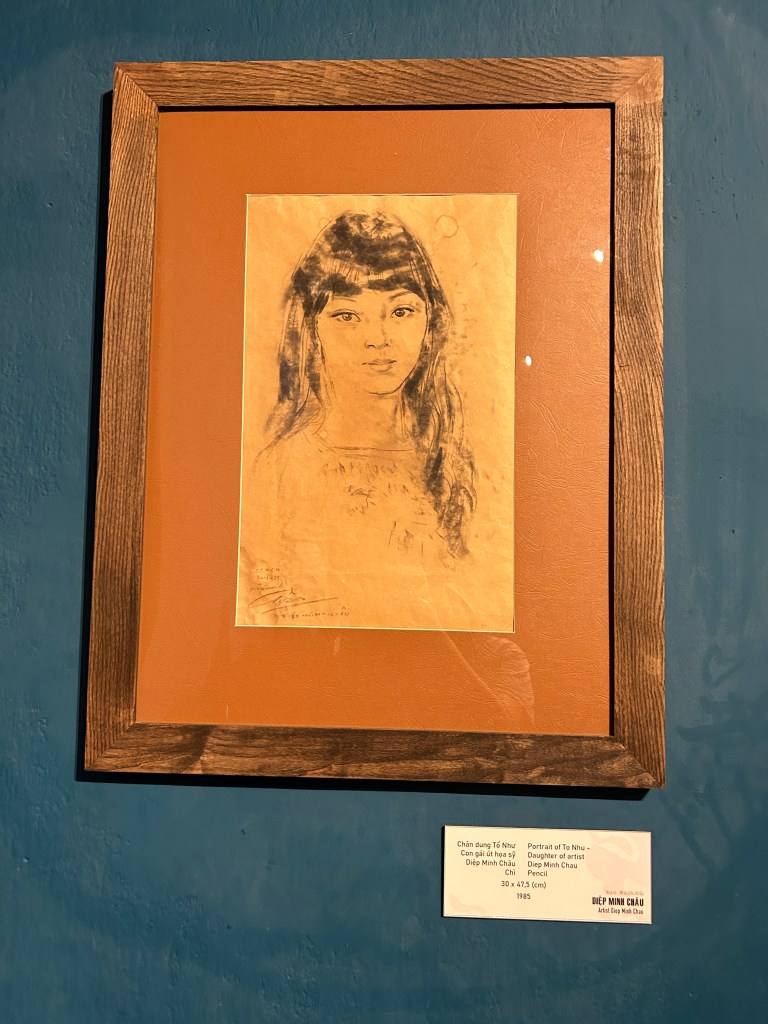

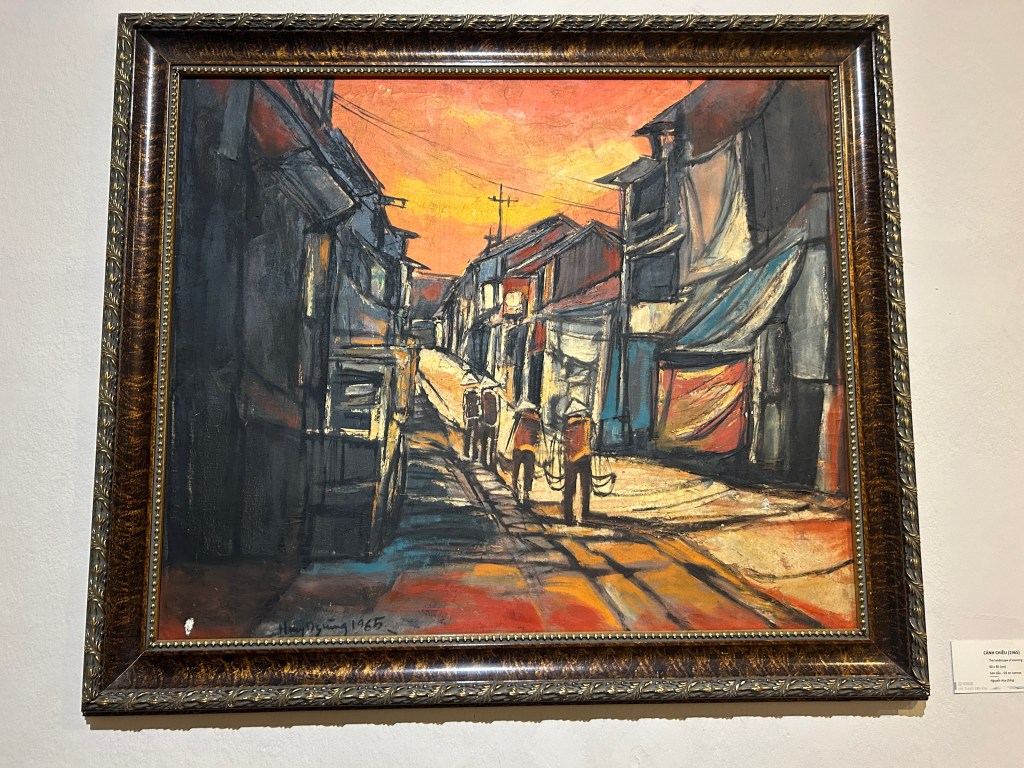

Rant aside, let’s talk about the collection within the museum, which is nationally important as it prides itself on the collection, preservation and exhibition of fine artworks typical of the Vietnamese people, especially in Ho Chi Minh City and the South of Vietnam. The ground floor focuses on both domestic and international items while the next level similarly displays both paintings and sculptures from leading Vietnamese and international artists of the last 50 years. The paintings are displayed there include big names on the scene such as Trinh Cung, Do Quang Em, Diep Minh Chau and Nguyen Gia Tri. The third floor holds a collection of historic artefacts ranging from seventh century to early twentieth century, featuring Champa and earlier civilisations such as Oc Eo archaeological site in Mekong Delta.

One of the highlights of the museum is undoubtedly the national treasure found in Nguyen Gia Tri’s Central South and North Spring Garden. As you can see, the image I took of said work was not a complete picture due to the monumental size at 540×200 cm of lacquer on wood. This massive undertaking was Nguyen’s swan song that was created when the country was in strife during wartime, it was the artist expressing his wish for unity and happiness in his homeland.

The poem unscripted on either sides of the work goes as such: The fragrance of flowers spreads in the direction of the wind. Bright moon with its shadows reflects on the clear water surface.

The Use of Lacquer as an Art Form

The use of lacquer as a painting material began with the innovations of artists working at the École des Beaux Arts de l’Indochine (EBAI) in Hanoi, during the French colonial period. The divide between art versus craft as well artists versus artisans, was a sensitive issue in this period, as it also involved the cultural politics of the ex-French colony. The very same discourse also interestingly appeared in Japan where decorative ornamental art forms raised similar debates of their standing within the hierarchy of Western Art especially in the 19th Century where cross-cultural artistic exchange between Japan and France was at its peak.

Unsurprisingly, this distinction between the French “artist” and the Vietnamese “artisan” indicated an implication indicative of the hierarchy of position and values which saw its repercussions over in the reception of the fledging field of lacquer painting. Tri was revered as the artist who shifted the genre most decisively from the ‘lesser’ realm of art and craft, making him a national hero in more ways than one.1

In a Nutshell

This important museum might not have an imposing stature, but is a key point that houses key artefacts that are testament to history as of HCM’s finest through architecture, art and culture. It also provides a continuation narrative of Vietnam’s story of art up till the present through the newer exhibits. The experience, unlike other museums which invite you to an exclusive, sometimes unreachable experiences that entice their visitors to join the exclusive club of cognisant experience, draws you in instead with humility and straightfoward connection. In the words of Camille Pissaro, ‘Blessed are they who see beautiful things in humble places where others see nothing.’ Let’s hope that the future visitors of museums in HCM will start to put down their phones and cameras and enjoy the gems in museums for what they truly are.

Leave a comment