Everyone knows of this mysterious place called the mind, but few can describe it. Even fewer can describe what it looks like because no one has seen it for real. I would bet that if one is asked to even hazard a guess at what it looks like, this attached image of an iceberg depicting Freud’s theory where the consciousness only takes up a mere 10 percent, represented by the visible layer of the iceberg might come up a few times. Here, he postulated that the real deal is buried and inaccessible, somewhere also known as the subconscious. This crucial theory was significantly born in the early days of 1915 and has been something of great interest to me in recent years.

As Socrates once said, knowing what you don’t know is the key to ultimate wisdom. Thanks to Sigmund Freud, the world now knows that there is a great wealth of information that is submerged in the murky depths of the waters of the mind, desolate and off-limits. I am one of the few people who can proudly say that I have stolen a glance at this unseen part of my mind. My journey to this mysterious metaphorical place began through hypnotherapy which primarily engages with the subconscious to make new suggestions and some re-chiselling of the inaccessible area of the metaphorical giant ice block. The effects can be monumental and I formed new habits and ways of thinking. Yes, I can fully attest that the subconscious is rework-able, and if one is committed enough, that frosty jagged slab could well become a beautiful sculpture.

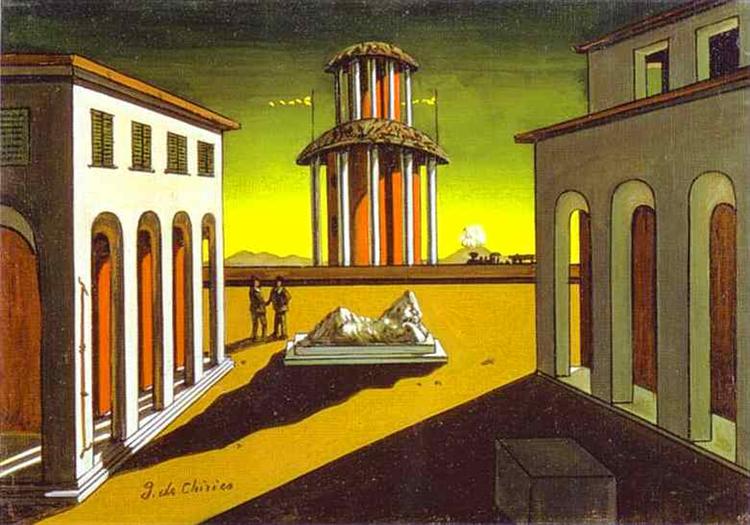

It must be out of pure coincidence where one night, I was listening to a hypnotherapy session on recording and had a mini lightbulb moment. I had just shown a child in my class the works of De Chirico on the that very same day a few hours before. The boy in question was interested in Pinterest images of liminal spaces (places that look abandoned, sad, surreal and frankly creepy) for his art project. Researching further on the subject led me to an iconic painting by Giorgio De Chirico on Google entitled The Soothsayer’s Recompense. Beholding the poetically titled work gave me a sudden tingling sense of deja vu and I found the landscape to be eerily similar to the place I navigated mentally while under hypnosis.

What made this moment so special for me was that in most circumstances, one would certainly be inclined to agree that when critically analysing a piece of art we chance upon can often be a hit and miss. That is the beauty of subjectivity, right? Varying assumptions and evaluations are made based on their personal experiences and life story. In this rare case, I was spot on in my original assessment of the works being reminiscent of my hypnotic ‘mind scenes.’ I was not far off, as reading further revealed that the artist himself termed these metaphysical canvases as ‘paintings of the mind.’ Derived from the Greek word meta ta physika (“after the things of nature”); alluding to an idea, doctrine, that falls outside the human sense of perception.1 It is indeed not a surprise For De Chirico who was brought up in Greece to be fascinated by foundational Hellenic philosophy to be fascinated by such concepts.

To paint the big picture, I will use the most relevant example. Our brain is considered a physical, tangible thing. The mind however, is another matter altogether despite it being an inextricable word that is almost always lined to the brain, falling under the umbrella of what comes ‘after nature’. Tell me something, have you ever seen your mind? Indeed, a quick Google search on the brain versus the mind explains that while the former acts as the headquarters of bodily functions, the latter is by contrary, an abstract concept that overseas reasoning, morality and understanding. The mind, by contrast, cannot be defined as something with corporeality. This brings us to the crossroads between to the world of metaphysics, the materiality as well as the after-materiality of things represented in these paintings in question that ‘cannot be seen.’ These images usually feature the contradiction between time and space, isolation and connection and reality versus illusion. Looking at a metaphysical painting entices the viewer into an experience similar to dreams and analysis where every detail within the pictorial frame holds pertinent meaning.

The critic Hearne Pardee also commented on the usage of bizarre layouts in such images, where the ‘dynamic exuberance is replaced by methodical composition, as though fastidious fabrication could generate visions.’ 2 These odd placements also sometimes feature peculiar pairings, urging one to reflect on their relationship and significance, imploring one to peel back the multiples layers of one’s psyche. The mystery of the peculiar environment is further deepened through the manipulation of light and shadow, drawing one’s curiosity to run wild. There is also conversely, a sort of warmth and comfort in belonging there. Why would it not be? It’s the only part of you that you have access to brought on by comforting, everyday objects found scattered around. It feels safe. It is home, literally the deepest part of one’s being where one’s innate essence abides. This sense of familiarity is further intensified by some sense of recognition of the mundane objects we all know, just positioned in illogical ways. Here, nothing seems to be as it is, yet everything seems to be in place. It is eerie but familiar. There is the tangible mixed up with the ethereal.

In the Soothsayer’s Recompense, one can see the multiple layers of De Chirico’s mental essence being artfully layered upon the canvas, stroke by stroke. De Chirico paints his shared sense of loneliness with the Greek statue identified as Ariadne, the Cretian princess who was spurned by Theseus after he made use of her to escape the legendary labryinth after he finished off the Minotaur. He made a promise to be with her after he escaped if she lent him a hand, but failed to deliver his promise. The jilted lover lounges in solitude in the middle of the square, seemingly between two states of being awake and sleeping, notably not unlike the state one is in when under hypnotic influence. Through his Italian heritage and immediate experience, De Chirico also naturally included the quintessential Italian piazza as a visual frame that binds all the strange objects together. Here, time is a philosophical construct where the sky looms melancholically dark over the scape. The time on the clock and the dark shadows scattered around the picture do not match up. The grouping of ancient Ariadne, the modern train and the infinite piazza all present a theme of obvious anachronism. Furthermore, the palm trees, although possibly symbolic of the childhood surroundings of De Chirico, are also exotic in origin where the tropical sunshine is very much absent from this melancholic scene.3 This is a mind-scape. This is what the mind, or rather, the subconscious looks like. Journeying here, one can bring back fragments of it to their waking reality.

Indeed, as C.G. Jung once famously said, ‘unless you make the subconscious conscious, it will direct your life and you will call it fate. Every time I waltz into the landscape of my mind, I bring a souvenir back with me. By uniting pieces of my repressed thoughts and my waking consciousness, I thrive and grow in countless ways. For I have a whole world to conquer, much more than a sheer Italian town square. It is would be a waste to leave it all up to fate.

Leave a comment