“Here’s looking back at you”—not just a clever turn of phrase, but an ancient invocation. Across time and terrain, one shape appears again and again: the eye. Watchful, brilliant, and blue as a summer sky, it stares from glass beads in Turkish markets, flickers in hieroglyphs buried beneath Egyptian sands, and dances on bracelets worn along the sunlit shores of Greece. These are no mere ornaments. They are shields. Wards. Symbols carved from the collective fear of envy, of unseen harm, of glances that wound. They tell stories—timeless ones—of protection, mystery, and belief in the invisible.

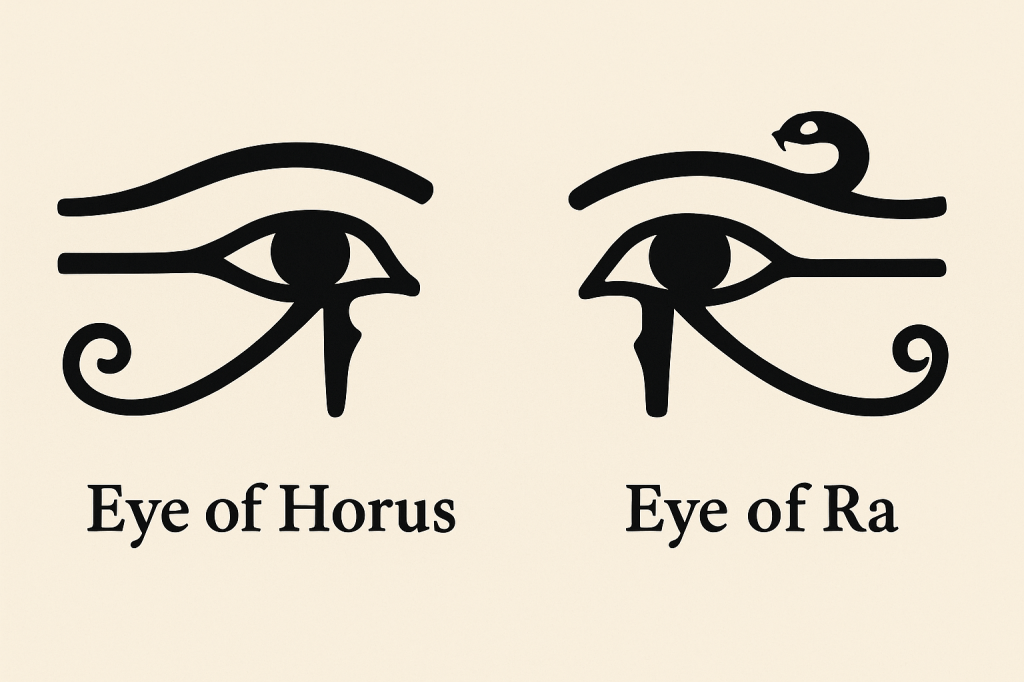

Along the golden sands of Egypt, the eye was more than decoration—it was divine. The Eye of Horus, torn in myth and healed by magic, symbolized protection, balance, and the eternal dance between chaos and order. It was said that Horus, the falcon-headed god of kingship, lost his eye in battle with his uncle Set. Restored by the gods, that eye became sacred, stylised with sweeping lines and a teardrop curve, resembling a falcon’s gaze—sharp, divine, protective. This process of injury and healing mirrored the waxing and waning of the moon cycle, further endowing The Eye of Horus its lunar associations. It was also worn by the living, buried with the dead, and used even in a system of measurement— its parts representing precise fractions to measure grain.

But not all eyes were soft. Egypt had another: the Eye of Ra, a symbol of fire, fury, and solar wrath. Associated with the cobra goddess Wadjet, it was said to spit flames in defense of the pharaoh, to punish with light and heat. Where the Eye of Horus was restorative, the Eye of Ra was destructive—a right-facing gaze that belonged to the sun, not the moon. You can still see it in the rearing cobra on royal crowns, poised to strike. One eye guards. The other avenges.

Prompt: “ancient Egyptian temple wall relief at Kom Ombo depicting the Eye of Horus (Wedjat) carved in sandstone.”

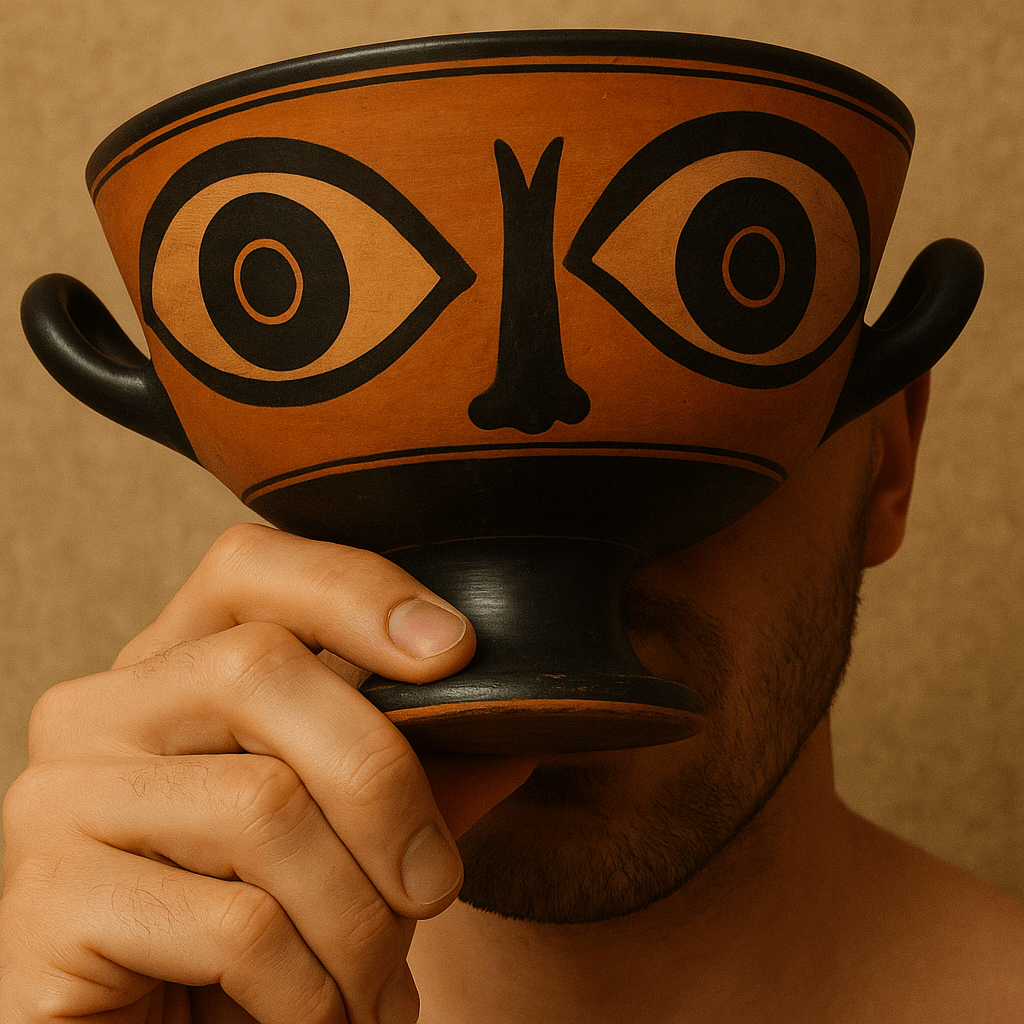

The symbol endured—reborn in ancient Greece as the mati, a blue eye with a gaze just as potent, just as protective. Round, blue, and unblinking, it was everywhere—from amulets and earrings to ceramic plates and roadside shrines. Its purpose was to absorb envy, to deflect the invisible arrows of ill intent. The philosopher Plutarch even theorised that the human eye was capable of emitting unseen beams capable of harming children, animals, and beauty itself. Blue-eyed people, he claimed, were the most dangerous—perhaps the reason the mati is so often painted in that very hue. Like the ancient Chinese belief in countering poison with poison, the mati turns the eye’s danger back on itself — warding off harm with harm’s own symbol. To this day, Greeks may offer compliments with a quick “Na mi se matiasis!”—don’t curse me with your gaze. The eye, here, lives quietly in modern life: mystical, everyday, protective.

Prompt: “Ancient Athenian trireme warship with a blue mati painted on the prow.”

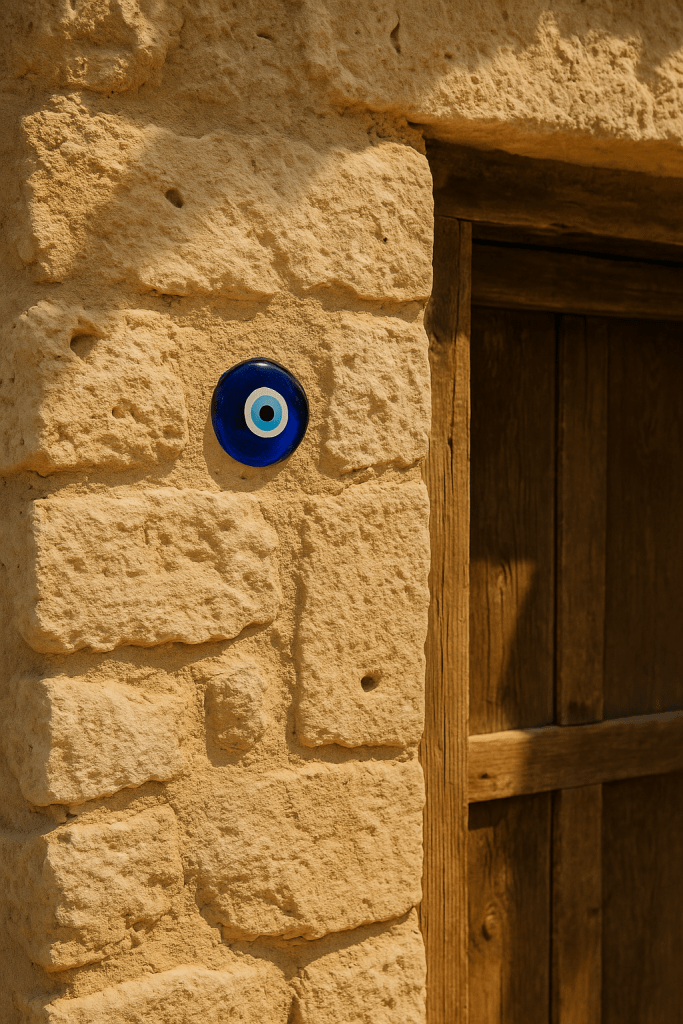

In Turkey, too, the belief persists—vivid, visible, and handmade. The nazar boncuğu, crafted from deep blue glass with concentric white and black rings, hangs in windows, dangles from wrists, swings from car mirrors, and rests gently on newborns’ chests. Its history winds back through Anatolia, Central Asia, and ancient Mesopotamia. Archaeological finds show that even in Sumerian times, people fashioned eyes from stone and clay to guard against the curse of envy. In modern Turkey, giving someone a nazar is an act of love, a gesture that says, “I see what might harm you—and I will help you hold it off.” In artisan villages like Görece and Nazarköy, the glass is still blown by hand, passed down from elder to apprentice, from fire to charm. In a world of complexity, this simple bead continues to carry a quiet promise.

Created with ChatGPT (GPT-5), October 2025.

Through the shadowed alleys and sun-drenched piazzas of southern Italy, the fear of the evil eye—malocchio—lingers too, though here the symbol shifts. Less a gaze, more a gesture, the protection comes in the form of the corno: a twisted horn, usually red, often small, carried in pockets or worn around necks. Its roots stretch back to Neolithic fertility rituals, Roman phallic amulets, and the cult of Priapus—gods and symbols bound to life, virility, and protection. While the eye looks back, the horn pushes forward. It repels. It defends. It stands not for sight, but strength.

Prompt: “A traditional Neapolitan doorway with a red corno horn amulet hanging above the entrance.”

Across all these cultures, all these centuries, one truth remains: we are wary of the glance that lingers too long, the admiration that carries a shadow, the praise that hides a curse. And so we have created symbols—not to erase that fear, but to meet it. An eye for an eye, in the most literal sense. Whether it’s the peaceful eye of Horus, the burning gaze of Ra, the round blue mati, the glimmering nazar, or the primal corno, each is an answer to the same unspoken question: How do we protect what we love from what we cannot see?

Leave a comment