Manueline architecture has always puzzled me. Standing before its wildly intricate façades, I feel admiration and confusion in equal measure. It is beautiful—but not in a logical or orderly way. It looks like an artistic experiment that could have failed… yet somehow didn’t.

Even its name feels oddly familiar yet distant. Most people recognise the term, but know almost nothing about it—including, very often, the person standing right beside me.

Emerging in Portugal at the turn of the sixteenth century, Manueline architecture was born at a moment when the country saw itself poised at the edge of the known world. Sea routes were opening, maps were being redrawn, and faith, empire, danger, and discovery were tightly entwined. Architecture responded with what feels like theology carved in stone: complexity as submission to mystery. These buildings seem to insist that incomprehensibility, devotion, and grandeur belong together—that to worship is, in part, to accept what cannot be neatly explained.

Although the style takes its name from King Manuel I, the term Manueline itself was coined centuries later by Francisco Adolfo de Varnhagen, after he was struck by the splendour of the Jerónimos Monastery. Originally, the label encompassed architecture, sculpture, and painting; today, it is most closely associated with architectural form.

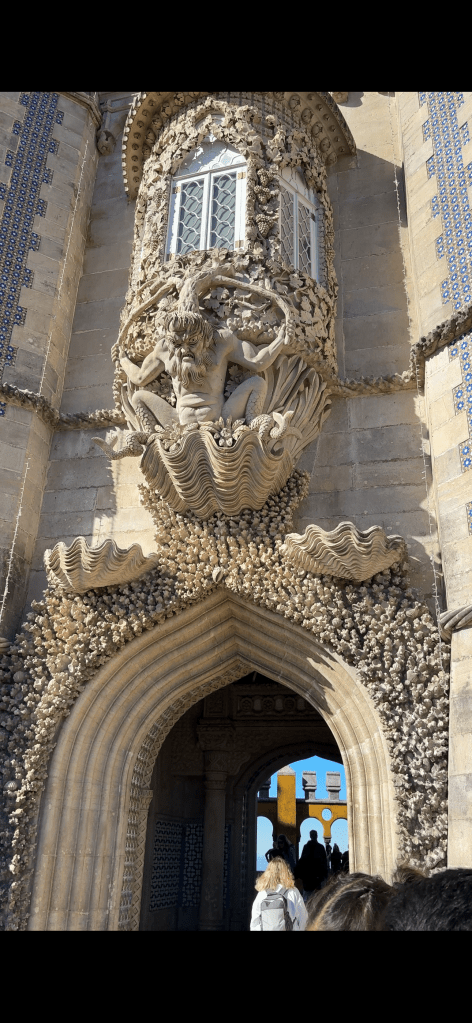

At first glance, Manueline buildings can feel chaotic, improvisational, even irrational. Late Gothic structures are overwhelmed by exuberant ornament drawn from Portugal’s maritime world, natural environment, and newly encountered territories. Conical pinnacles erupt upward; ropes, knots, anchors, and coral coil across stone surfaces; leaves, vines, and botanical motifs sprout with almost unchecked vitality. Christian symbols and royal emblems jostle with forms inspired by distant lands.

These decorations do more than embellish. They take over the building. Elements that should merely support structure creep into it; ornament becomes architecture. In this sense, Manueline feels like an unpolished predecessor of the Baroque, collapsing distinctions between architecture, sculpture, and surface into a single visual experience.

Yet Manueline fits uncomfortably into the established timeline of Western art. It is too late to be truly Gothic, too restless and unconcerned with classical perfection to be Renaissance, and too restrained—at least in comparison—to be Baroque. It belongs fully to none of these categories. Instead, it feels like a tide-logged sea chest washed ashore after a dangerous voyage: valuable not because it is pristine, but because it survived.

For this reason, scholars continue to debate whether Manueline is even a unified “style.” It may be better understood as a historical phenomenon—one rooted in a precise and volatile moment in Portuguese life. It shaped monasteries, fortresses, civic buildings, and even overseas territories, carrying with it the anxieties and ambitions of an empire grappling with the unknown.

One feature distinguishes Manueline clearly from other late Gothic forms: its vernacular character. Massive construction campaigns demanded speed and scale, drawing in builders who were often less formally trained. Structural problems were solved empirically rather than theoretically, leading to over-embellishment, non-functional decorative columns, and misread classical schemes.

Yet these “flaws” are precisely what give Manueline its strange appeal. The style is sophisticated and naïve at once—anti-erudite, inventive, and disarmingly human. It reveals a moment when imagination outran theory, and ambition outweighed restraint.

Thinking about Manueline inevitably brings me to Antonio Gaudí. Though separated by centuries, both resist classical order, favour organic forms, and refusal to separate architecture from sculpture. Both are deeply spiritual, defiantly excessive, and slightly mad in the best possible way. Each sits awkwardly within their own time, insisting that buildings can breathe, contort, and feel alive.

This creative surge was not confined to architecture. Painting and sculpture flourished during this period as well, particularly under Flemish influence. Large retables from the early sixteenth century embrace density, layering, and emotional intensity—visual counterparts to the overloaded stone façades of Manueline buildings. Across media, the impulse is the same: meaning emerges through accumulation rather than restraint.

Ultimately, Manueline architecture reveals the mindset of an empire confronting uncertainty. It celebrates risk, faith, ambition, fear, and triumph in stone. It blurs the boundaries between architecture, sculpture, and fantasy, rejecting clarity in favour of wonder.

Despite—or perhaps because of—its chaos, it endures. Not as a perfect style, but as a testament to imagination pushed to its limits. Maybe that is the real miracle: what looks like madness was, in the end, a kind of genius.

Further Reading/ Bibliography

1) Encyclopaedia Britannica, “Manueline,” Britannica.com, accessed December 2025, https://www.britannica.com/art/Manueline

2) Pedro Dias, Dalila Rodrigues, Fernando Grilo, and Nuno Vassallo e Silva, The Manueline: Portuguese Art during the Great Discoveries (Museum With No Frontiers/MWNF, 2017).

Leave a comment