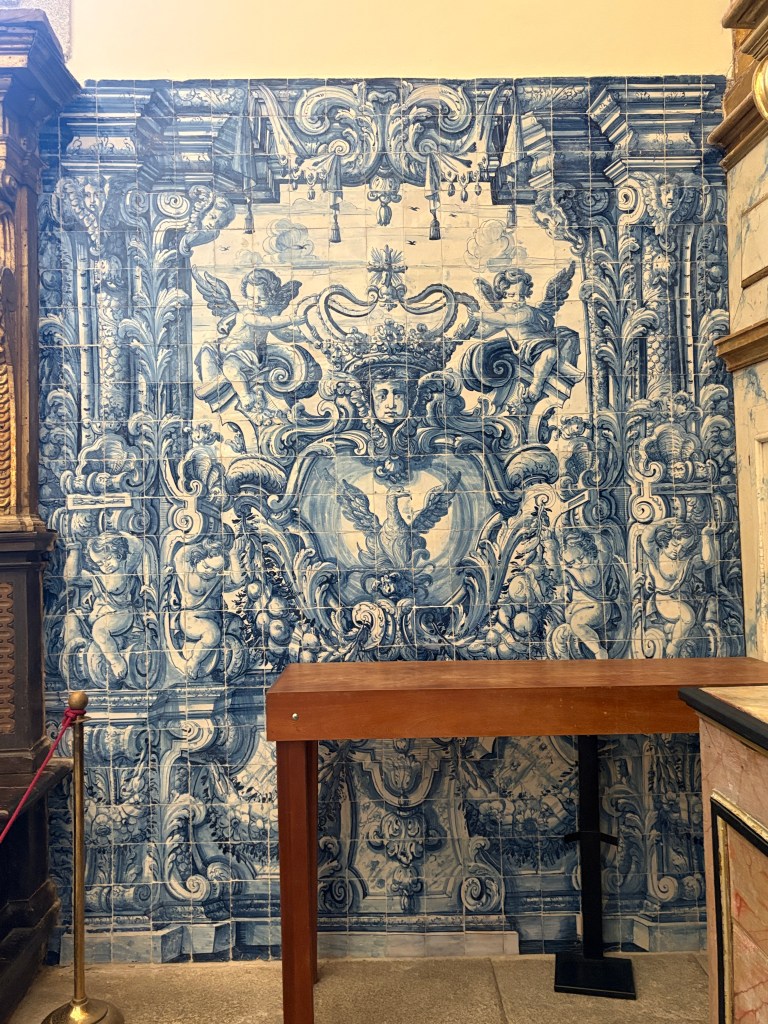

When we look at the name Azulejos, we think we are looking at colour, but we are really looking at walls that learned how to speak. It is a common misunderstanding—understandable, given that azul means blue and that some of the most iconic Portuguese tile work seems to be overwhelmingly in the cool hue—that the name azulejos itself is defined by colour. In reality, blue was never their essence. These icons of Portuguese visual culture trace their origins to Islamic traditions brought to the Iberian Peninsula by the Moors, who pioneered glazed tile-making long before it became a national emblem. The very word azulejo itself comes from the Arabic al-zulaij, meaning polished stone or small smooth tile, pointing not to hue but to surface and material.

In Portugal, Azulejos were never simply decorative. They functioned as architectural surfaces that carried stories across walls, streets, and everyday life. Their mode of viewing differed fundamentally from encountering a painting in a museum. These were not images meant for fixed, frontal contemplation, but narratives designed to be experienced in motion—glanced at while passing, noticed again while waiting, and gradually absorbed through repeated return.Reading hence, took place over time rather than in a single moment. Integrated into the structure of buildings, tiles also protected walls from dampness and helped regulate interior temperatures, while simultaneously transforming architecture into a storytelling medium.

This dual function of narrative practicality finds its stunning example on the tiled façade of the Capela das Almas, often encountered along the busy Rua de Santa Catarina. Here, azulejos move outward onto the exterior of the building, confronting the street directly. Scenes from the lives of Saint Catherine of Alexandria and Saint Francis of Assisi unfold across the chapel’s walls, turning the structure itself into a public devotional surface. Most viewers encounter these images while walking past—shopping bags in hand, phones briefly raised—sometimes neglecting to enter the chapel itself. Yet this fleeting mode of viewing was precisely intended. The panels are legible from a distance, readable in fragments, and absorbed gradually through repetition. Sacred narrative does not require stillness or ritualised entry; it spills into everyday urban life.

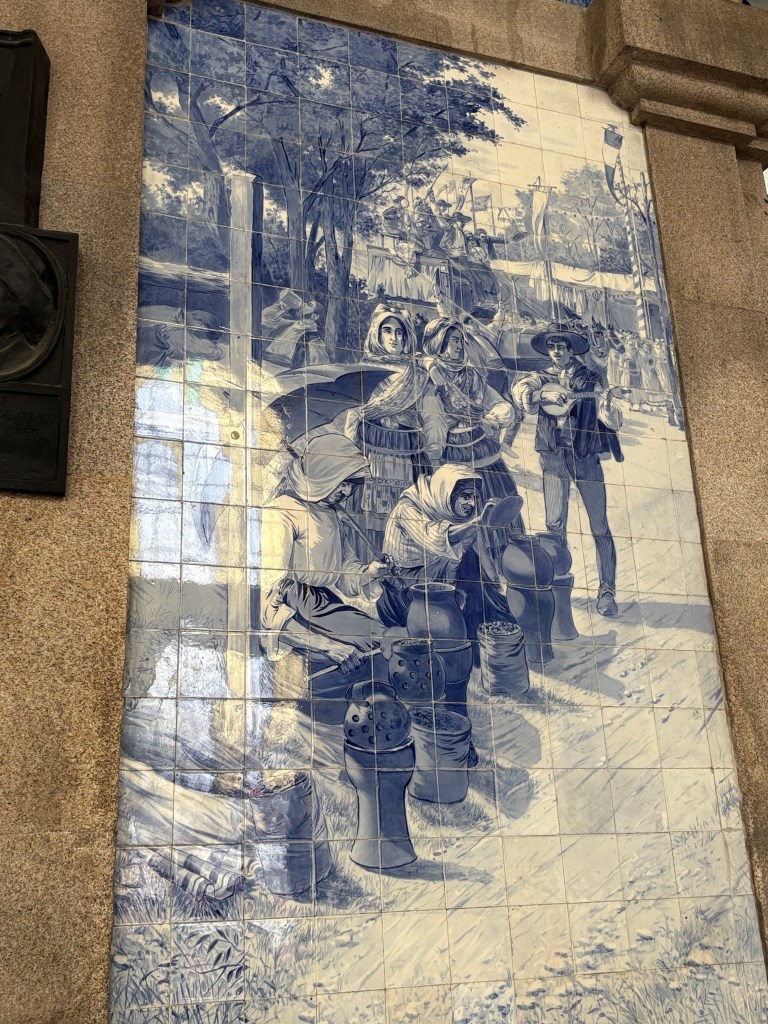

If Santa Catarina demonstrates how azulejos function as exterior architecture—visible, instructive, and encountered in passing—the interior of the São Bento Railway Station reveals a different narrative rhythm. Here, azulejos operate within a civic space defined by waiting and transit. More than 20,000 tiles line the station’s interior, depicting scenes from Portuguese history, rural life, and transportation. Designed in the early 20th century by Jorge Colaço, the panels transform the station into a vast historical frieze. Unlike Santa Catarina’s fleeting encounter, São Bento rewards duration: travellers linger, glance up repeatedly, and gradually piece together the narratives while waiting for their trains. History here becomes something absorbed over time, embedded into the rhythms of movement and pause.

During the Age of Discovery of the 15th and 16th centuries, Portugal emerged as a global power, generating unprecedented wealth that allowed tile production to flourish on an extraordinary scale. The nation’s long history of maritime expansion helps explain this seamless merging of structure and image. Already shaped by Islamic tile traditions, Portuguese visual culture was further informed by global trade that international material aesthetics in which surface and structure were inseparable. For instance, from Indian textiles—such as stylised birds and branching motifs drawn—as well as from French Rococo decorative panels. The very predilection towards blue and white pairings themselves came from Dutch and Chinese inspirations shaped by Dutch Delftware and Chinese blue-and-white porcelain encountered through global trade although it is important to note that azulejos did come in a great variety of other colours as well.

It is therefore unsurprising that this visual language came to dominate the streets and civic spaces of Portuguese cities, where walls were not silent backdrops but active carriers of memory and meaning. The craft of azulejo-making remains very much alive in Portugal today, with contemporary artists and designers continuing to reinterpret the medium, ensuring that these speaking walls remain part of the country’s lived architectural language rather than relics of the past.

A lost art form it is not, the craft of Azulejos is very much alive today in Portugal, with designers and artists of today still putting their very own spin on this art form.

American Ceramic Society. (n.d.). Azulejos: A Portuguese tradition influenced by globalization. Ceramics.org.

https://ceramics.org/ceramic-tech-today/azulejos-a-portuguese-tradition-influenced-by-globalization/

Azulejo magic: Exploring the beauty of Portuguese tiles. (n.d.). Google Books.

https://www.google.com.sg/books/edition/Azulejo_Magic_Exploring_the_Beauty_of_Po/gV5OEQAAQBAJ

Leave a comment